THE SOLUTION

Native Plants: Good for your Yard, Good for the Forests

3 things you can do

|

1. Reduce Invasive Seed Rain

The most important step you can take is to cut “survival rings” around ivy-infested trees. English ivy (Hedera helix) goes to seed when it climbs vertically, so severing vines saves the tree and slow ivy’s rate of spread. Do this for Atlantic ivy (Hedera hibernica), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and wild clematis (Clematis vitalba), too. Don’t pull vines down; it could damage the tree and endanger you - let them “wither on the vine.” Girdle invasive trees (typically English holly, hawthorn, and laurel). Saw a ¼ inch “kerf” around the stem at breast-height), or cut and peel off a section of bark in spring when the bark is "slipping." Invasive trees will resprout, so break off new shoots to eventually starve the plant – this may take years. If you want faster results and have weighed the risks and benefits of herbicide applications, you may find licensed professionals on the Herbicide Info page. The Step by Step guide offers a detailed understanding of restoration practices so you can do-it-yourself or direct hired help. If you're in a wetland or slide-prone area, check Environmentally Critical Area status with your local jurisdiction before clearing invasive vegetation. Other invasive seed rain sources in Western Washington include: English and Portuguese laurels, European hawthorn, pyracantha, cotoneaster, bird cherry, wild plums, European mountain ash, Japanese honeysuckle, Poison hemlock, Bittersweet nightshade, and knotweed (see SeedRain Species page). Knotweed illustrates the need for careful "best practice" techniques necessary to eradicate this water-loving plant. Knotweed can't be left to spread - it displaces native plant food sources required by native insects - the base of food chains that feed salmon fingerlings. It erodes streambanks and spreads widely, primarily by root/plant fragments establishing downstream, and by yard waste dumpings. Cutting or pruning knotweed will cause 20 times the root suckers, much like horsetail (native) or holly (invasive). Knotweed roots can grow 10 feet deep along streambanks, making manual removal impossible without causing erosion that can smother salmon eggs. Eradication of knotweed requires that infestations be left unpruned, to be treated by licensed professionals applying wetland-safe aquatic herbicides approved by the Dept. of Ecology. Follow-up treatments are likely necessary, along with erosion control and replanting of native plants. |

2. Go native!

Native plants feed the bugs that feed the birds in extended seasons. Lists of native plants may be found at: wnps.org (Washington Native Plant Society), nwf.org (plant-finder guide), and xerces.org (Xerces Society, focusing on pollinator species). Plant suggestions, plus landscaping plans can be found at: King County Native Plant Guide. A short list of habitat plants good for your northwest-of-the-Cascades yard include:

|

Plant evergreen conifers with woody debris or woodchip mulch to protect soil and slow stormwater runoff. Plant evergreen conifers with woody debris or woodchip mulch to protect soil and slow stormwater runoff.

3. Enhance the forest's soil “sponge” to

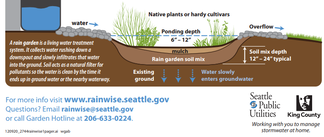

preserve water quality Any loss of tree cover or soil health will exacerbate flooding and stormwater pollution. "Stormwater" is rain run-off from roads, driveways, lawns, and combined stormwater-sewer overflows. Stormwater is considered the #1 source of toxins fouling Puget Sound and other water bodies. Plant diverse species for wildlife, but favor evergreen trees to shade out weeds and intercept twice the stormwater than deciduous trees during winter rain. Plant native evergreen conifers (Douglas fir, Western red cedar, Western hemlock, Sitka spruce, Grand fir) on appropriate-sized properties to accommodate their mature heights (avoid overhead and underground utilities). On smaller properties, plant shorter trees: Shore pine or Pacific Yew, or evergreen shrubs and groundcovers. Another way to recreate the forest sponge is to transform your lawn with a diversity of plants (see Step-by-Step Guide). Native plants are 4-5 times better at attracting native birds and pollinators. Improve your soil's sponge by spreading appropriate organic matter ("grass-cycling," leaves, and plant trimmings) or creating "habitat piles" that protect foraging birds. "Leave the leaves (!)" in messy areas for ground-nesting pollinators, and leave stumps intact as wildlife snags with rotting roots in the ground. In fire-prone regions, avoid kindling-like fuel in fire-safe zones around structures. Ask local tree services for arborist’s woodchips to mulch trees (keep woodchips 4 inches away from plant stems). Request logs, splitting for better ground contact, and plant near these "nurse logs." Spread woodchips at variable depths, avoiding contact with stems of desired plants, and leave some bare soil for pollinators. Berm woodchip mulch up to 1-ft deep to filter runoff from driveways and dog runs. If you're in a slide-prone area, educate yourself about the causes of landslides starting with a webinar by Greenbelt Consulting, plus getting professional advice as needed. If you're not in a slide-prone zone, consider a raingarden to capture and absorb rainfall from your roof. An excellent summary of “green infrastructure” to reduce stormwater runoff can be found at Tox-Ick.org. |